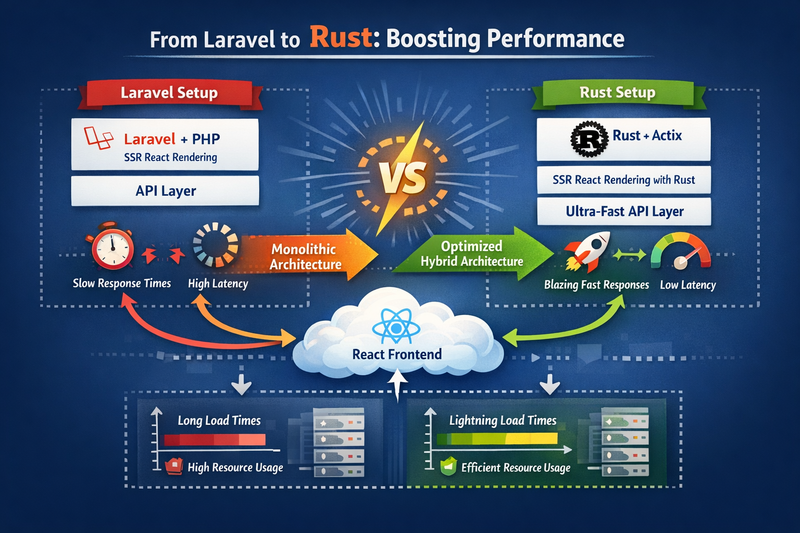

Introduction: Why “High-Performance Backend” Matters

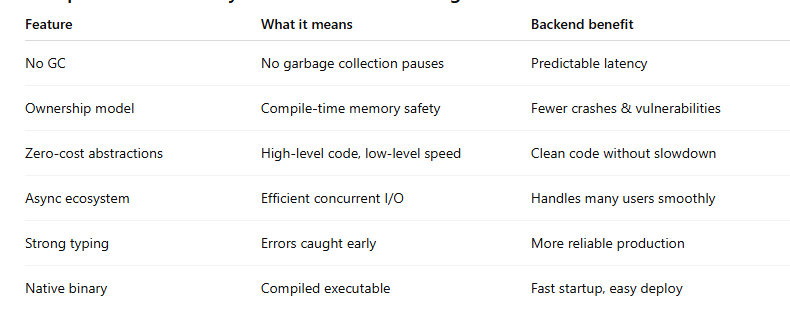

What Makes Rust a Great Backend Language?

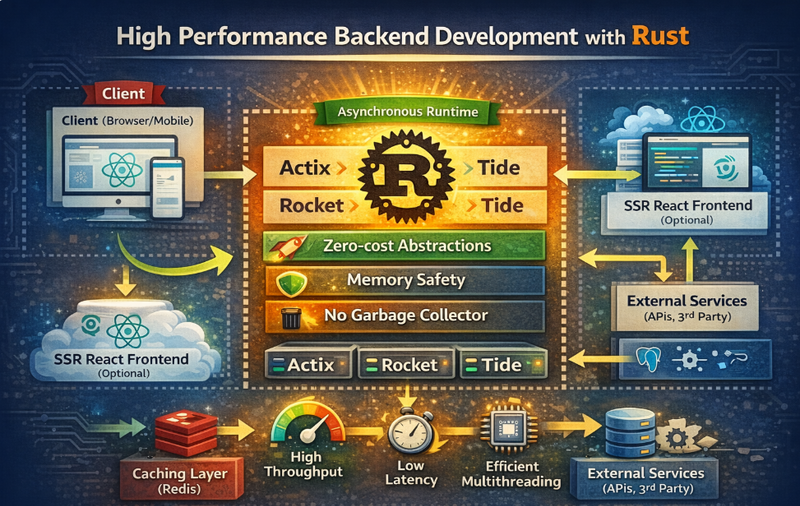

Step 1: Choose a Rust Backend Style (Architecture)

Step 2: The Performance Principles You Must Follow

Step 3: Build a High-Performance Rust API (Step-by-Step)

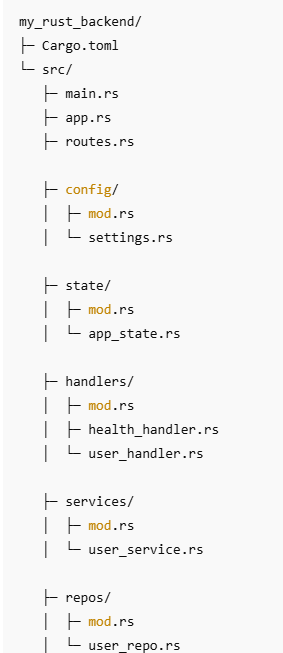

Step 4: Project Structure (Clean and Maintainable)

Step 5: Coding Example (Rust Backend)

Step 6: Why This Example Is “High-Performance Friendly”

Step 7: Production Architecture (What You Add Next)

Step 8: Rust Backend Performance Checklist

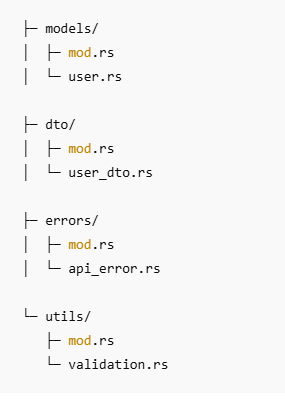

Comparison Table: Why Rust Works Well for High Performance Backends

Clean Rust Backend Folder Structure (handlers / services / repos)

Step-by-Step Implementation Example (Minimal, Realistic)

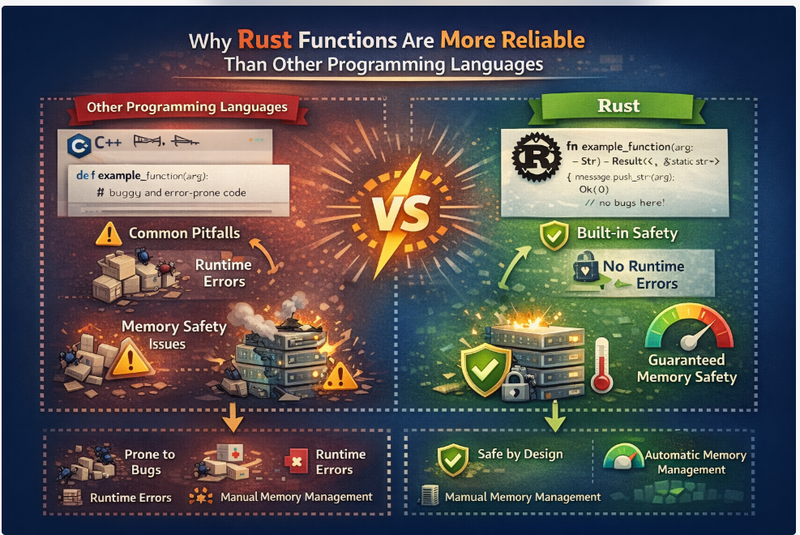

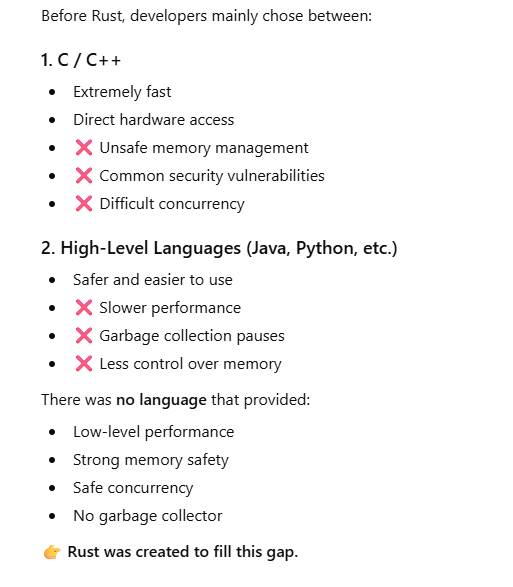

Comparison of rust pl with other pl

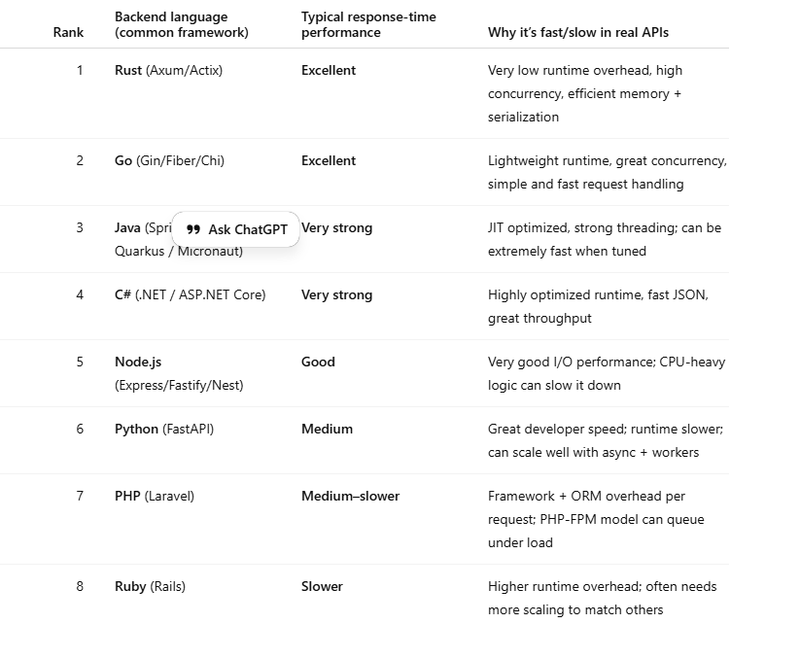

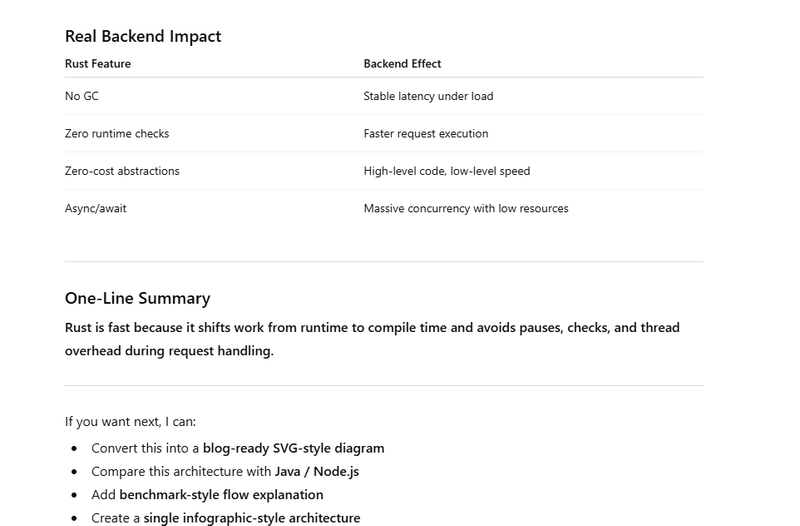

why rust provide faster response time

Rust is a modern systems programming language that’s become a serious choice for backend development because it combines high performance, strong security, and predictable reliability—without relying on garbage collection.

In this blog, you’ll learn why Rust performs so well for backend systems, how to design a clean backend architecture, and how to build a simple high-performance API step by step with clear code examples.

Introduction: Why “High-Performance Backend” Matters

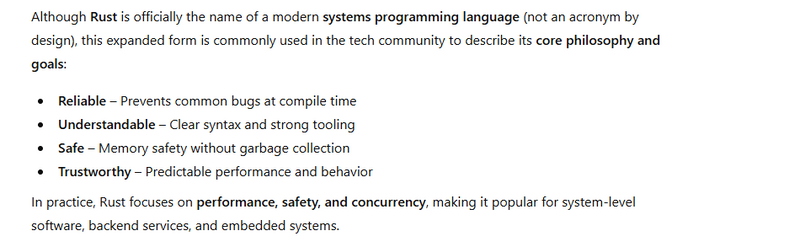

RUST stands for Reliable, Understandable, Safe, and Trustworthy.

A “high-performance backend” isn’t only about speed. It’s about handling real-world pressure:

Sudden spikes in traffic

Many concurrent users

Heavy database activity

Real-time data processing

Consistent response time under load

Rust shines here because it helps you build backends that are:

Fast(close to C/C++ performance)

Safe (memory safety by design)

Stable (no random GC pauses)

Scalable (excellent concurrency model)

What Makes Rust a Great Backend Language?

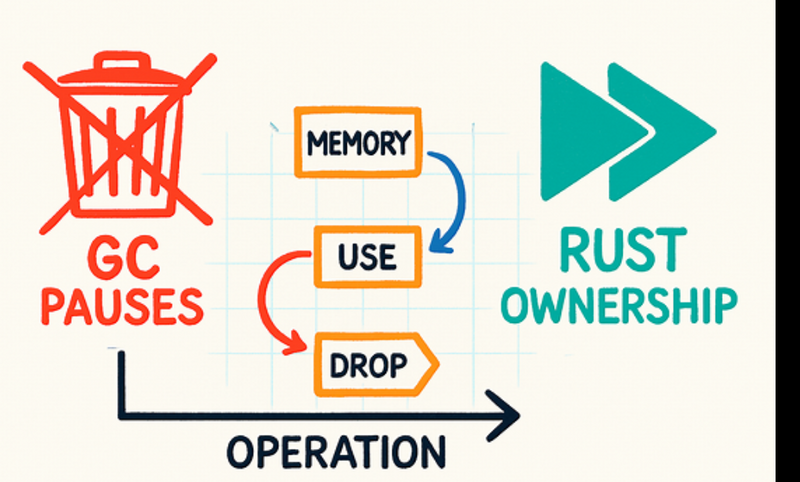

Memory Safety Without Garbage Collection

Rust prevents common memory bugs at compile time:

use-after-free

buffer overflow patterns (many cases)

null pointer style errors (Rust uses Option)

Backend benefit: fewer crashes, fewer security vulnerabilities, fewer production surprises.

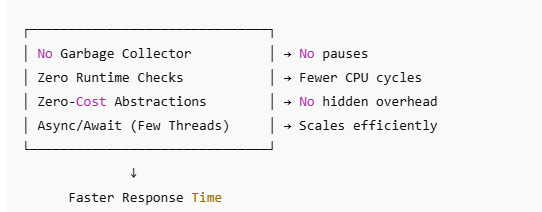

Predictable Latency (No GC Pauses)

Languages with garbage collection can sometimes pause to clean up memory. These pauses are usually small but can become painful at scale.

Rust does not use a GC, so response times are more predictable.

Backend benefit: stable p95/p99 latencies, especially under load.

Zero-Cost Abstractions

Rust lets you write expressive code (iterators, traits, generics) that compiles down to efficient machine code.

Backend benefit: clean code without hidden slowdowns.

Efficient Concurrency (Async + Safe Multithreading)

Rust’s type system helps prevent data races, and its async ecosystem enables high concurrency.

Backend benefit: handle many requests efficiently with fewer resources.

Step 1: Choose a Rust Backend Style (Architecture)

Before writing code, choose how your backend is structured.

Common Rust Backend Architectural Patterns

A) Simple Layered Architecture

Handlers (HTTP layer): parse requests, return responses

Services (business logic): rules, validations, workflows

Repositories (data access): database queries, caching

B) Clean Architecture (Recommended for larger projects)

Domain: core rules, models (framework-free)

Application: use-cases (business workflows)

Infrastructure: DB clients, cache clients, external API clients

Interface / Transport: HTTP/gRPC handlers, request parsing

This reduces long-term chaos and makes performance tuning easier.

## Step 2: The Performance Principles You Must Follow

Keep the “hot path” clean

Your hot path is the code executed on every request. For better performance:

Avoid unnecessary allocations (String creation, cloning)

Prefer borrowing (&str) over owning (String) where possible

Validate quickly, exit early on errors

Use efficient serialization and minimal response size

Minimize blocking calls

Blocking calls (like slow DB calls or file I/O) can slow response time if not handled properly.

In Rust backends, you typically:

Use async for I/O heavy operations

Use worker tasks for CPU heavy operations

Step 3: Build a High-Performance Rust API (Step-by-Step)

We’ll build a small API with:

Fast routing

Basic validation

Clear separation of handler/service

In-memory storage (for simplicity)

Structured responses

API we’ll build

GET /health → quick health response

POST /users → create user

GET /users/:id → get user

Note: This is a minimal example to teach structure and performance habits. You can later replace the in-memory store with a database.

Step 4: Project Structure (Clean and Maintainable)

A good structure keeps performance tuning and scaling straightforward.

Example structure:

main.rs (server bootstrap)

routes.rs (route wiring)

handlers/ (HTTP handlers)

services/ (business logic)

models/ (data models)

store/ (data storage)

Step 5: Coding Example (Rust Backend)

Below is a compact version in one file so you can follow easily. In real projects, split into modules.

Example: High-Performance API Skeleton (Async HTTP)

use axum::{

extract::{Path, State},

http::StatusCode,

routing::{get, post},

Json, Router,

};

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

use std::{

collections::HashMap,

sync::{Arc, RwLock},

};

use uuid::Uuid;

#[derive(Clone)]

struct AppState {

// RwLock is fine for demo. For high write throughput, consider other approaches later.

users: Arc<RwLock<HashMap<String, User>>>,

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Serialize)]

struct User {

id: String,

name: String,

email: String,

}

#[derive(Debug, Deserialize)]

struct CreateUserRequest {

name: String,

email: String,

}

#[derive(Debug, Serialize)]

struct ApiResponse<T> {

ok: bool,

data: Option<T>,

error: Option<String>,

}

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

let state = AppState {

users: Arc::new(RwLock::new(HashMap::new())),

};

let app = Router::new()

.route("/health", get(health))

.route("/users", post(create_user))

.route("/users/:id", get(get_user))

.with_state(state);

let addr = "127.0.0.1:3000";

println!("Server running on http://{addr}");

let listener = tokio::net::TcpListener::bind(addr).await.unwrap();

axum::serve(listener, app).await.unwrap();

}

async fn health() -> (StatusCode, Json<ApiResponse<&'static str>>) {

(

StatusCode::OK,

Json(ApiResponse {

ok: true,

data: Some("ok"),

error: None,

}),

)

}

async fn create_user(

State(state): State<AppState>,

Json(req): Json<CreateUserRequest>,

) -> (StatusCode, Json<ApiResponse<User>>) {

// Step 1: Validate quickly (fast fail)

if req.name.trim().is_empty() {

return (

StatusCode::BAD_REQUEST,

Json(ApiResponse {

ok: false,

data: None,

error: Some("Name is required".to_string()),

}),

);

}

if !req.email.contains('@') {

return (

StatusCode::BAD_REQUEST,

Json(ApiResponse {

ok: false,

data: None,

error: Some("Email looks invalid".to_string()),

}),

);

}

// Step 2: Create user (minimal allocations)

let id = Uuid::new_v4().to_string();

let user = User {

id: id.clone(),

name: req.name.trim().to_string(),

email: req.email.trim().to_string(),

};

// Step 3: Store (write lock held for short time only)

{

let mut map = state.users.write().unwrap();

map.insert(id, user.clone());

}

(

StatusCode::CREATED,

Json(ApiResponse {

ok: true,

data: Some(user),

error: None,

}),

)

}

async fn get_user(

State(state): State<AppState>,

Path(id): Path<String>,

) -> (StatusCode, Json<ApiResponse<User>>) {

// Read lock (fast and concurrent)

let maybe_user = {

let map = state.users.read().unwrap();

map.get(&id).cloned()

};

match maybe_user {

Some(user) => (

StatusCode::OK,

Json(ApiResponse {

ok: true,

data: Some(user),

error: None,

}),

),

None => (

StatusCode::NOT_FOUND,

Json(ApiResponse {

ok: false,

data: None,

error: Some("User not found".to_string()),

}),

),

}

}

Step 6: Why This Example Is “High-Performance Friendly”

This design follows several performance best practices:

1) Short lock duration

Locks are held only while inserting/reading data, not while validating or building responses.

2) Fast validation (fail early)

Bad requests return quickly, saving CPU and preventing wasted work.

3) Minimal extra cloning

We clone only where needed to safely return ownership of data.

4) Async server with efficient scheduling

The runtime can handle many concurrent connections without a “thread per request” approach.

Step 7: Production Architecture (What You Add Next)

A real backend usually includes:

Common components

Database (PostgreSQL/MySQL)

Cache (Redis)

Queue (Kafka/RabbitMQ/SQS)

Observability (logs, metrics, tracing)

API gateway / reverse proxy

Typical Rust Backend Architecture

API Layer: routes + handlers (thin)

Service Layer: business rules

Repository Layer: DB queries + caching

Worker Layer: background jobs (email, reports, processing)

Step 8: Rust Backend Performance Checklist

Use this checklist when building real systems:

Avoid unnecessary allocations in hot paths

Prefer borrowing (&str) over String when possible

Keep DB calls async and efficient (indexes, query tuning)

Use connection pools

Cache smartly (not everything)

Offload CPU-heavy tasks to workers

Add timeouts and rate limits

Measure p95/p99 latency regularly

Comparison Table: Why Rust Works Well for High Performance Backends

Clean Rust Backend Folder Structure (handlers / services / repos)

What Each Folder Means (Simple & Practical)

handlers/ (HTTP layer)

Purpose: Handle HTTP details only

Parse request body/query/path params

Call the service layer

Convert service result into HTTP response

Keep handlers thin.

services/ (Business logic layer)

Purpose: Rules + workflows

Validate business rules (not just syntax)

Decide what repo calls are needed

Orchestrate operations (create user, send event, etc.)

This is the “brain” of your application.

repos/ (Data access layer)

Purpose: Database/Cache access only

CRUD queries

Transactions

Mapping DB rows to models

No business rules here.

Step-by-Step Implementation Example (Minimal, Realistic)

Below is a small example of a User Create + Get API using this structure.

1) models/user.rs

use serde::Serialize;

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Serialize)]

pub struct User {

pub id: String,

pub name: String,

pub email: String,

}

2) dto/user_dto.rs (request/response bodies)

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

#[derive(Debug, Deserialize)]

pub struct CreateUserRequest {

pub name: String,

pub email: String,

}

#[derive(Debug, Serialize)]

pub struct ApiResponse<T> {

pub ok: bool,

pub data: Option<T>,

pub error: Option<String>,

}

3) errors/api_error.rs (central API error)

use axum::http::StatusCode;

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct ApiError {

pub status: StatusCode,

pub message: String,

}

impl ApiError {

pub fn bad_request(msg: impl Into<String>) -> Self {

Self { status: StatusCode::BAD_REQUEST, message: msg.into() }

}

pub fn not_found(msg: impl Into<String>) -> Self {

Self { status: StatusCode::NOT_FOUND, message: msg.into() }

}

}

4) repos/user_repo.rs (in-memory example)

Later you replace this with DB (Postgres/MySQL) without touching handlers much.

use std::{collections::HashMap, sync::{Arc, RwLock}};

use crate::models::user::User;

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct UserRepo {

users: Arc<RwLock<HashMap<String, User>>>,

}

impl UserRepo {

pub fn new() -> Self {

Self { users: Arc::new(RwLock::new(HashMap::new())) }

}

pub fn insert(&self, user: User) {

let mut map = self.users.write().unwrap();

map.insert(user.id.clone(), user);

}

pub fn find_by_id(&self, id: &str) -> Option<User> {

let map = self.users.read().unwrap();

map.get(id).cloned()

}

}

services/user_service.rs (business logic)

use uuid::Uuid;

use crate::{

dto::user_dto::CreateUserRequest,

errors::api_error::ApiError,

models::user::User,

repos::user_repo::UserRepo,

};

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct UserService {

repo: UserRepo,

}

impl UserService {

pub fn new(repo: UserRepo) -> Self {

Self { repo }

}

pub fn create_user(&self, req: CreateUserRequest) -> Result<User, ApiError> {

let name = req.name.trim();

let email = req.email.trim();

if name.is_empty() {

return Err(ApiError::bad_request("Name is required"));

}

if !email.contains('@') {

return Err(ApiError::bad_request("Email looks invalid"));

}

let user = User {

id: Uuid::new_v4().to_string(),

name: name.to_string(),

email: email.to_string(),

};

self.repo.insert(user.clone());

Ok(user)

}

pub fn get_user(&self, id: &str) -> Result<User, ApiError> {

self.repo

.find_by_id(id)

.ok_or_else(|| ApiError::not_found("User not found"))

}

}

state/app_state.rs (shared app dependencies)

use crate::{repos::user_repo::UserRepo, services::user_service::UserService};

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct AppState {

pub user_service: UserService,

}

impl AppState {

pub fn new() -> Self {

let user_repo = UserRepo::new();

let user_service = UserService::new(user_repo);

Self { user_service }

}

}

handlers/user_handler.rs (HTTP glue only)

use axum::{

extract::{Path, State},

http::StatusCode,

Json,

};

use crate::{

dto::user_dto::{ApiResponse, CreateUserRequest},

state::app_state::AppState,

};

pub async fn create_user(

State(state): State<AppState>,

Json(req): Json<CreateUserRequest>,

) -> (StatusCode, Json<ApiResponse<crate::models::user::User>>) {

match state.user_service.create_user(req) {

Ok(user) => (

StatusCode::CREATED,

Json(ApiResponse { ok: true, data: Some(user), error: None }),

),

Err(e) => (

e.status,

Json(ApiResponse { ok: false, data: None, error: Some(e.message) }),

),

}

}

pub async fn get_user(

State(state): State<AppState>,

Path(id): Path<String>,

) -> (StatusCode, Json<ApiResponse<crate::models::user::User>>) {

match state.user_service.get_user(&id) {

Ok(user) => (

StatusCode::OK,

Json(ApiResponse { ok: true, data: Some(user), error: None }),

),

Err(e) => (

e.status,

Json(ApiResponse { ok: false, data: None, error: Some(e.message) }),

),

}

}

handlers/health_handler.rs

use axum::{http::StatusCode, Json};

use crate::dto::user_dto::ApiResponse;

pub async fn health() -> (StatusCode, Json<ApiResponse<&'static str>>) {

(

StatusCode::OK,

Json(ApiResponse { ok: true, data: Some("ok"), error: None }),

)

}

routes.rs (route wiring)

use axum::{routing::{get, post}, Router};

use crate::{handlers::{health_handler, user_handler}, state::app_state::AppState};

pub fn create_router(state: AppState) -> Router {

Router::new()

.route("/health", get(health_handler::health))

.route("/users", post(user_handler::create_user))

.route("/users/:id", get(user_handler::get_user))

.with_state(state)

}

main.rs (bootstrap)

mod routes;

mod handlers;

mod services;

mod repos;

mod models;

mod dto;

mod errors;

mod state;

use crate::state::app_state::AppState;

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

let state = AppState::new();

let app = routes::create_router(state);

let listener = tokio::net::TcpListener::bind("127.0.0.1:3000")

.await

.unwrap();

axum::serve(listener, app).await.unwrap();

}

Comparison of rust pl with other pl

Why rust provide faster response time

No Garbage Collector (No Pause Time)

What Rust Does

Rust uses compile-time memory management instead of a runtime garbage collector.

Why This Improves Response Time

No GC “stop-the-world” pauses

No unpredictable latency spikes

Every request finishes without interruption

Example

Scenario: Payment API handling 10,000 requests/sec

GC-based language: occasional pause (10–50 ms) → slow responses

Rust: consistent sub-millisecond handling

Impact:

➡ Stable and predictable response times, especially under load.

- Ownership & Borrowing (Zero Runtime Checks)

What Rust Does

Rust enforces memory safety at compile time, not runtime.

Why This Improves Response Time

No reference counting overhead

No runtime safety checks

Direct memory access without indirection

Example

fn process(data: &str) -> usize {

data.len()

}

This:

Allocates nothing

Copies nothing

Runs as fast as raw machine code

Impact:

➡ Faster execution per request.

-

Zero-Cost Abstractions

What Rust Does

High-level features compile down to optimal machine code.

Why This Improves Response Time

No hidden performance penalties

Abstractions disappear at compile time

Example

let total: i32 = numbers.iter().map(|n| n * 2).sum();

Compiles to:

A tight loop

No intermediate collections

No virtual calls

Impact:

➡ Expressive code without runtime slowdown.

-

Async / Await Without Thread Explosion

What Rust Does

Rust’s async model is non-blocking and lightweight.

Why This Improves Response Time

Thousands of connections handled by a few threads

No thread context-switch overhead

Faster request scheduling

Example

async fn handler() -> String {

fetch_from_db().await;

"OK".to_string()

}

One thread can manage thousands of async requests

Blocked I/O doesn’t block the thread

Impact:

➡ Lower latency under high concurrency.

-

Fearless Concurrency (No Locks in Hot Paths)

What Rust Does

Prevents data races at compile time.

Why This Improves Response Time

Less locking

No race-condition retries

More parallel execution

Example

use std::sync::Arc;

use std::thread;

let data = Arc::new(vec![1, 2, 3]);

thread::spawn({

let data = Arc::clone(&data);

move || {

println!("{}", data[0]);

}

});

Safe concurrency without runtime checks.

Impact:

➡ Better CPU utilization, faster responses.

-

Minimal Memory Allocation

What Rust Does

Encourages stack allocation and reuse.

Why This Improves Response Time

Heap allocations are expensive

Stack memory is fast and cache-friendly

Example

fn handle(req: &str) {

let status = "OK"; // stack allocation

}

Impact:

➡ Lower allocation cost per request.

-

Predictable Cache-Friendly Memory Layout

What Rust Does

Uses contiguous memory structures.

Why This Improves Response Time

Better CPU cache utilization

Fewer cache misses

Example

struct User {

id: u64,

active: bool,

}

Stored compactly in memory, improving access speed.

Impact:

➡ Faster data access during request handling.

-

Single Static Binary (Faster Startup)

What Rust Does

Compiles to a single optimized binary.

Why This Improves Response Time

No runtime VM startup

Faster cold starts (important for autoscaling)

Impact:

➡ Faster first request after deploy or scale-up.

rust programming language docs

rust programming language u tube

Top comments (0)